Côte d’Ivoire’s Containment of Jihadist Threats: A Provisional Success?

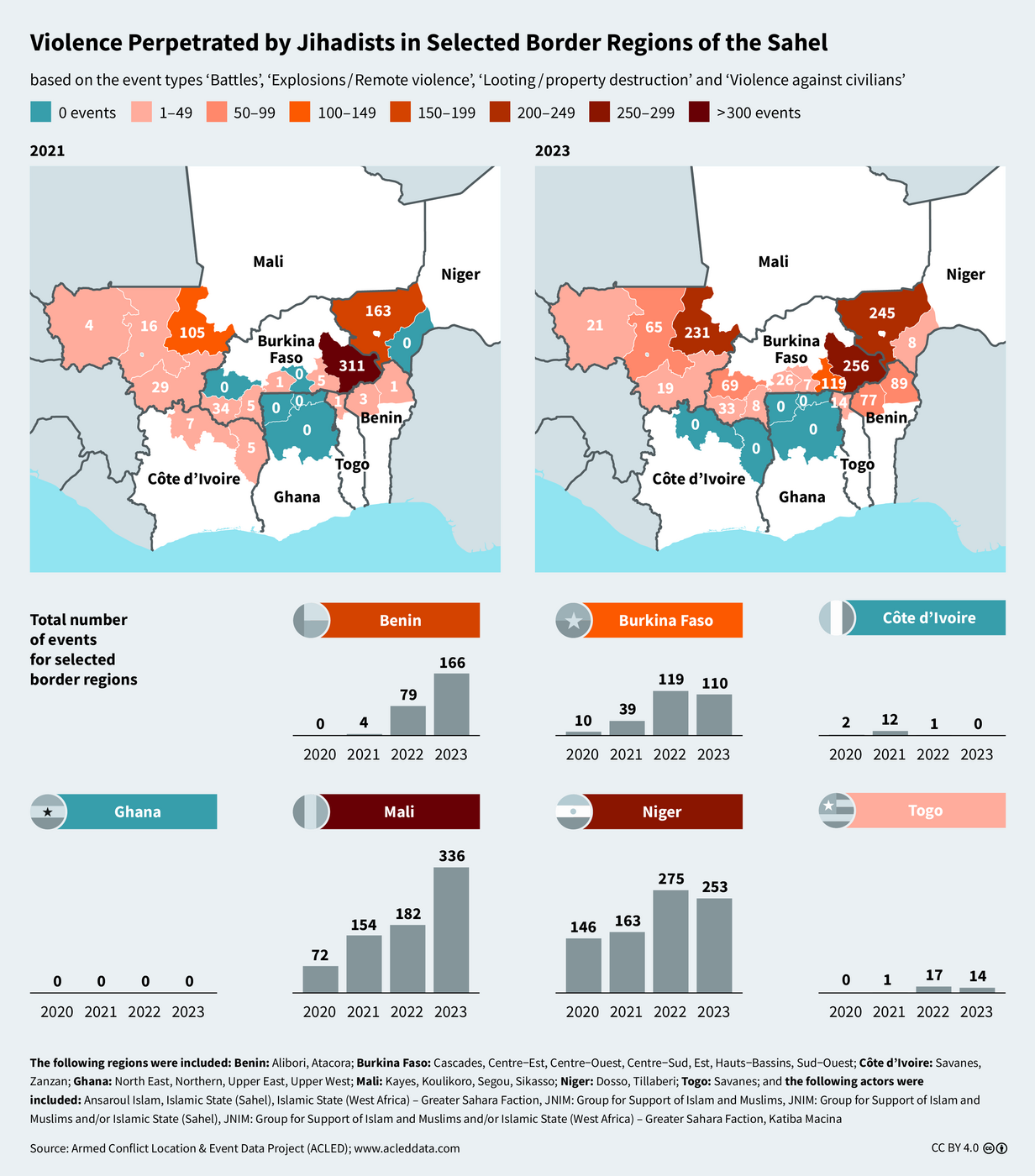

Megatrends spotlight 40, 08.10.2024Jihadist violence has spread from the Sahel to some – but not all – of the coastal countries of West Africa. While Togo and Benin are increasingly affected by attacks, the opposite is true of Côte d’Ivoire (and Ghana). But the Ivorian success stands on shaky foundations, as Denis Tull explains.

© picture alliance / REUTERS | Luc Gnago

Between 2020 and 2022, northern Côte d’Ivoire experienced several attacks attributed to the al-Qaeda-affiliated Katiba Macina. In the most serious case, in June 2020, jihadists killed fourteen Ivorian soldiers in the village of Kafolo near the border to Burkina Faso. The government responded with a comprehensive package of measures to counter the jihadist threat and there have been no attacks in Côte d’Ivoire since mid-2022. However, the heavy security presence in the north is not unproblematic. How should we assess the security situation? And to what extent is it a success of Ivorian counter-terrorism?

The Ivorian Response to Jihadist Threats

The Ivorian government’s efforts to combat the infiltration of jihadist groups from neighbouring countries revolve around enhanced security. Abidjan has massively increased its military and security presence in its northern regions, both in terms of quality and quantity. The number of police officers in the region has at least doubled since 2020 (to around 4,000) and the strength of the gendarmerie has tripled (to around 10,000). In addition, a further 1,500 soldiers have been deployed to the north. The equipment and facilities of military and police units were also upgraded (drones, vehicles, etc.). In addition, an “Operational Zone North” commanded by an army general was set up to coordinate all operational military and security measures and all relevant intelligence was pooled under the umbrella of the “Centre de renseignement opérationnel antiterroriste” (CROAT). Government officials consider effective information and intelligence gathering to be the key to success. For this to be effective, they argue, good relations between citizens and the authorities and security forces are essential. That cannot be taken for granted in a country still struggling with the aftermath of a decade of civil war (2002–2012).

The Ivorian government has also instigated a series of socio-economic programmes worth around €49 million (2022–2025) to complement the security focus. As well as investments in infrastructure (including road and electricity networks) that have already been under way for several years, this includes youth job creation, vocational training, micro-projects and loans for small businesses. It is uncertain whether these short-term measures, which are familiar from many post-conflict contexts, will effectively promote stabilisation, in part because their coordination and management appear weak. So many donors and NGOs are currently engaged in “stabilisation efforts” in the north of Côte d’Ivoire that local observers and some diplomats have criticised the “incessant ballet” of organisations.

The decline in attacks is undoubtedly a partial success. However, government officials confess uncertainty over the extent to which this is actually attributable to their own policies, or whether there may be other causes at work.

The Strategic Calculations of Jihadist Groups

One potential explanation for the positive security trend could lie in the strategic calculations of the jihadist groups. At least in the short term, Côte d’Ivoire may not be their priority. In addition to Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, which remain their primary focus, the jihadists seem to be concentrating on “softer” targets in the coastal states, such as Togo and in particular Benin, where security capacity may be weaker. Benin was hit by 166 attacks in 2023 (equivalent to 14 attacks per month), although slightly fewer have been recorded so far this year (9 per month).

From an Ivorian perspective the status quo is ambivalent. As long as the jihadists concentrate on other targets, Côte d’Ivoire is at comparatively little risk. But it is also clear that jihadist successes in the Sahel are rippling out and could return to Côte d’Ivoire at some point. Nowhere is this more evident than in neighbouring Burkina Faso, where more than half of the national territory has now slipped out of the junta’s control. Côte d’Ivoire shares long and largely uncontrolled borders with Mali and Burkina Faso (532 km and 584 km respectively). In view of the increase in jihadist attacks in the southern regions of Mali (Kayes, Koulikoro, Ségou, Sikasso) and Burkina Faso (Cascades, Sud-Ouest, Hauts-Bassins), the risk of attacks in Côte d’Ivoire is heightened. These developments are already affecting the north of Côte d’Ivoire, and the number of Burkinabe refugees in the country has more than tripled since 2022. There are currently 58,000 refugees in the districts of Tchologo and Boukani. So far, they have been relatively well received by local communities and the government. However, security circles see them as a security risk. This explains why Abidjan has established its own reception and registration programme, rather than leaving refugee management to international aid organisations. The expulsion of 167 Burkinabe refugees in July of this year points to tensions.

From the Ivorian perspective, however, the problem in the Sahel is not limited to immediate security risks. The military juntas in the Sahel have made their antagonism towards most of their neighbours a trademark of their foreign policy. Bilateral relations between Côte d’Ivoire and the military regimes in Mali and Burkina Faso are at a low point and bilateral security cooperation has come to a complete standstill. At best there are informal and sporadic contacts between officials in the border region. Relations between Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso are particularly poor. Rhetorical broadsides from Ouagadougou towards Abidjan and even skirmishes between security forces in the border region make structured cross-border action against the jihadist groups implausible, at least for the time being. This situation obviously makes it easier for jihadist groups to operate.

No Attacks, But a Jihadist Presence

A lack of attacks does not mean that the north of Côte d’Ivoire can relax. The presence of members of jihadist groups has been confirmed. As in Ghana, the jihadists use areas close to the border to rest, recover and recruit, as well as for logistical purposes. There is also evidence of their involvement in financially lucrative unregulated trade in gold and cattle. The jihadists have established themselves in the local economy through various means (robbery, taxation, extortion and direct investment). Preexisting economic networks close to the border, which are often based on informal or illicit practices (including smuggling), are particularly susceptible to penetration by jihadist actors. This violent appropriation of resources has been described as the “jihadisation of banditry”. As well as jihadists it may also involve a broad spectrum of local actors (smugglers, bandits, militias, prospectors, middlemen, etc.). Some of these act opportunistically but are often forced to reach an accommodation with violent jihadists if they wish to retain a foothold in their markets. This local political economy and the associated relationships are central to understanding the mechanisms and dynamics of jihadist expansion, Plain poverty is a secondary factor, even though the Tchologo region on the border with Burkina Faso, for example, has one of the highest poverty rates in the country (62.8 percent).

In this context the increased military and security presence in the north is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it appears to have contributed to improving local perceptions of the security situation. On the other hand, there have been many complaints about extortion and corruption by military and security forces. This undermines the public trust upon which the security forces depend for information and intelligence. Numerous roadblocks, where money is extorted from citizens and traders, also undermine economic livelihoods. The frequency of roadblocks indicates that the Ivorian military and security forces are also serving their own financial interests, especially in the vicinity of markets and gold mines. In one case, no less than 14 roadblocks were counted on the 24 kilometres of road connecting Tengréla and Papara. Refugees also suffer extortion. About one third of Burkinabe refugees said that they had been required to pay bribes when crossing the border. Around 60 percent of refugees are Peul, who stand under general suspicion in Burkina Faso – and across the region – because this group accounts for a large proportion of the region’s jihadists. In the north of Côte d’Ivoire, too, it is mainly Peul who are suspected and arrested by the security forces. However, as experience in Mali shows, discrimination and arbitrary repression help the jihadists to recruit followers.

Outlook

Even though Côte d’Ivoire has been a target for jihadist groups since the attack in Grand-Bassam (2016), it should not be viewed solely through the prism of jihadist risk. The wider national political and economic context also deserves close attention. While the 82-year-old President Alassane Ouattara has succeeded in establishing a form of political hegemony in the aftermath of the civil war (2002–2012), this does not necessarily mean structural stability. The military mutinies of 2017 and the 2020 elections, in which over 100 people lost their lives, indicate the fragility of the political system. Discontent over Ouattara’s constitutionally and politically controversial bid for a third term could flare up again if he decides to stand in the 2025 presidential elections, as appears likely. There is already great frustration over restrictions on political freedom and curtailment of civil society activities. Above all, the gravity of the social and economic situation should not be underestimated. Although Côte d’Ivoire has enjoyed high growth rates over the past decade (averaging 6.7 percent), there is enormous dissatisfaction with the economic situation (poverty, purchasing power, unemployment, inequality). As seen recently in Nigeria and Kenya, that is potentially highly explosive.

Dr Denis Tull is a Project Director of Megatrends Afrika and a Senior Associate in the research division Africa and Middle East at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

The author would like to thank Paul Bochtler (SWP) for the analysis of the ACLED data, on which the chart is based.